As we sit down for our interview, Philippe Briand hastens to clear a space for me in the compact boardroom. The bright white room (save for a few conspicuous gold trophies) is taken up by a table filling most of the available space, and covered in papers. They contain various drawings, sketches and writing, some more detailed than others. Yet none of them have the frustrated feel of an idea that has been started and then discarded, but rather of an evolution of a fantastical new superyacht concept here, or a more streamlined hull for a family cruiser there.

Yacht racing is in his DNA, and growing up in La Rochelle with a father who was an Olympic Dragon Class sailor, he was exposed to all it entails at a very young age. But racing alone was not to be his destiny: “I understood very young that to win a race you have to have the best boat, and so I started to be interested about the technology and the design of the boat. The way to win a race, not just winning races,” he explains. “When I was 11 years old I started designing my own boats. Then, when I was 16, I was given the opportunity to have a yacht built under my own design, and then I just kept going!” This yacht was a 25 foot wooden racing yacht commissioned and built by a shipyard in Alicante. The yacht was successful and a further 11 were built.

When asked if he knew he wanted a career in yacht design he doesn’t miss a beat. “Yes of course. For me it was really my goal. I was a good pupil at school, and I started studying old books about naval architecture and learning things such as the handicap rule so I could apply it to my designs.” In the 1970s and 1980s the international yachting scene was dominated by the Ton Cup. “It was a fantastic event,” he says. “It was a great opportunity for young designers to experiment and design prototypes, because the budget was reasonable, and full-scale experimentation is very hard for them to access today. Every year we would come to the World Championship with a new boat, and we would compete against international designers from as far away as New Zealand and America.” Philippe counts Pelle Petterson, the Olympic-medal- winning sailor and yacht designer, among his inspirations. “I worked with him for two years when I was 18. As well as an accomplished sailor, he was a designer of production boats and maxis, and the designer and skipper of the Swedish America’s Cup boat, so he had a lot of versatility. I learnt a lot and I often think of him and that period of my life.”

He will readily admit that the thrill of a challenge is one of the driving forces behind his ever-increasingly ambitious and cutting-edge designs. “I like the competition. Not only as a sailor, but I also have this competitive spirit as a designer, which really motivates me. I like to look at existing boats, andI say ‘I would like to design a better boat!’ And so the criteria is sometimes performance, sometimes comfort, sometimes beautiful design. But my goal is always to design something better than before.” This spirit is clearly very strong indeed, because Philippe’s boats are nothing if not ground breaking, from the 42-metre Mari-Cha IV, which broke the record for fastest monohull crossing of the Atlantic in 2004, to the recently launched Grace E, a beautiful 73-metre superyacht built by Picchiotti Perini Navi.

“I don’t have a favourite boat as such, because I ultimately like all my designs for different reasons. But obviously I have special affections for yachts I have won races in, such as Freelance which won the Half Ton Cup in 1983, and Passion II which won the One Ton in 1984. I was totally at one with those boats, because I designed them and was also the skipper. I was also extremely happy when we won two awards in two years, one for best sailing yacht in 2012, Vertigo, and one for best motor yacht in 2011, Exuma.”

Exuma also just happens to be his first-ever motor yacht design, a considerable feat. He explains that what made him move into motor yacht design was this same competitive drive. “A motor yacht was a kind of challenge I’d never experienced before. We decided to enter the market in 2006 and believed the best way to be successful was to design something out of the box and very special.” He is referring to his Vitruvius line of designs, with their striking axe bows. “We were very fortunate with our first client, the owner of Exuma. I was in Monaco with a model of Vitruvius and he was immediately attracted. He quickly understood the philosophy behind the design and our ideas matched. He was a very qualified yachtsman and had already done a circumnavigation on a motor yacht. He said ‘I am totally crazy to trust a designer who never designed a motor yacht!’ But he did, and today he’s a friend!”

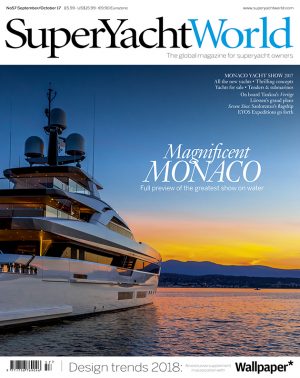

Galileo came next and Grace E has just been unveiled to critical acclaim at the Monaco Yacht Show. Yet Philippe shows no sign of living off past glory: “the work on the drawing board now is a 132-metre Vitruvius.” Asked if there is a market for it he looks surprised: “Of course! The building of the larger yachts was not really interrupted by the financial crisis. It is a trend which started in the 1990s and I believe the market is still sustainable. At the lower end of the industry, well it was like an engine in a cold winter. It was sleeping very well, but it’s definitely waking up. We certainly feel the recovery is there, and we have never received more enquiries about new boats than in 2014,” he says.

“In the late 2000s the industry went through a crisis which gave it no real opportunity to grow. But we need to remember that people expect designs in keeping with the times. We are not going to make a generation of 2007-style boats, we will make ones for 2020. You have to be on the edge of technology, ecology and efficiency. Otherwise people will buy second hand. So we really need to tell them that ‘yes, it’s possible to design a boat today for 2020, and this is our goal, and here is the technology’. And this is the role of the designer: to assemble all of that and propose it and say ‘yes, and this is the way we’re going to do it’.”

Over 12,000 yachts that he has designed are at sea today, ranging from dinghies to family Jeanneaus and, of course, radical superyachts. It is not hard to imagine that some of the most famous boats of the next decade will also originate in the La Rochelle and Chelsea offices of Philippe Briand Design, and, joined by his “muse” and partner Veerle Battiau, known as Cookie to their inner circle, the future is certainly looking bright for this Frenchman.